Bread & Roses

The right to self-determination. A phrase that is bandied about fairly regularly. One that is now immediately associated with violence, loss of life and the grand old web of occupational politics. When one breaks down the phrase into its component words, none of them actually exist. Who really has the right to self-determination? Whether it is a state, constantly in turmoil, or at a smaller but equally powerful level, an individual who wants to exercise free choice—in terms of gender . . .who really has the right?

Women’s Day is replete with advertisements, memes and WhatsApp forwards. Gimmicks that are both mocked and acknowledged. But where do we really place when it comes to the rights of not just women, but people all over the world who are looking for that elusive right to self-determination?

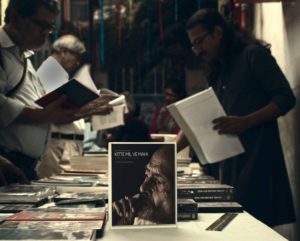

‘For Bread and Roses’, the monthly screening organised by the Peoples Film Collective on the occasion of International Working Women’s Day, saw two films—told from two very different, yet similar perspectives, both on the subject of rights.

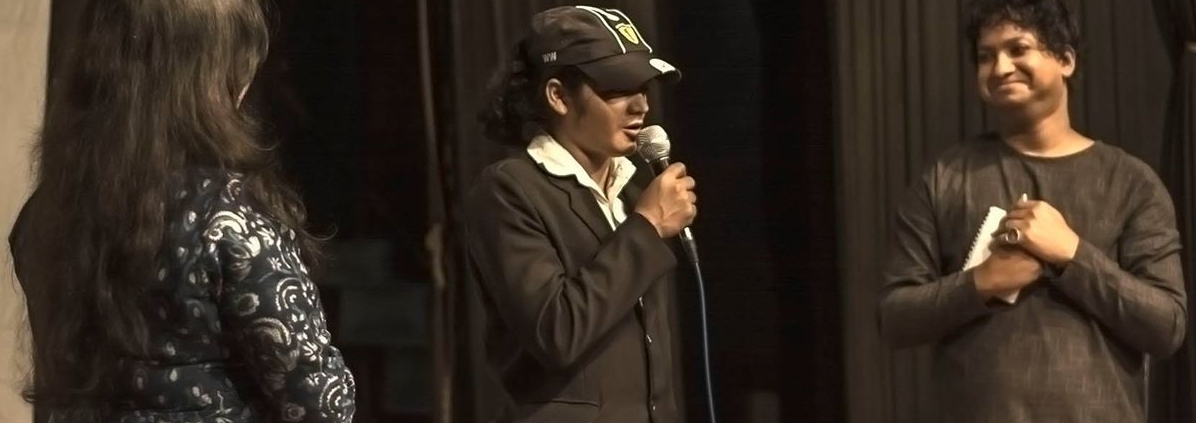

The first film Doud (The Frontrunner), directed by Debalina and Payoshni Mitra is a documentary on the life and struggles of athlete Pinki Pramanik. It takes us through the events in her life and how her rights as an individual and athlete were taken away from her by a false accusation of her having raped an woman, and the archaic gender determination ‘laws’ that were laid out by sporting bodies. Laws—that as Payoshni Mitra says and rightly so— are regressive. Pinki, who currently works with the Eastern Railways and has returned to the world of sports, spoke about how it was nice to watch the film after three long years, in the discussion after the screening. When asked about the reactions to her return to athletics in her village and in the city, she mentioned that while the reactions were not so tangible in the village, her supporters in the city were very happy.

Activist Anindya Hajra spoke next, connecting the transgender movement to the Working Women’s Day. As opposed to putting transgender and working women’s movements in separate boxes, Anindya spoke about transgender rights essentially being part of the rights of the working class and, for many, rights of working women. Anindya reminded the audience about the history of transgender workers in Bengal’s jute mills, about present-day transgender workers in various factories and industrial sectors and how that aspect is usually not brought into the public discourse or in working class or labour movement discourse. Anindya spoke extensively about the right to choose ones gender identity and how it is wrong to define a person by gender. Speaking about the changes in the National Legal Services Authority (NALSA) agreement of 2014, Anindya mentioned that the drafts, which are not being made public, show that gender is being defined through a highly ‘medical’ process. This completely takes away the right given to people who do not identify with the male-female binary to determine their own gender. While some Universities in India do now have the space (in admission forms and so on) for people to identify as ‘other’, as one of the audience members asked, they still don’t feature in the prevention of sexual harassment guidelines when it comes to actual protection.

Nirnay, directed by Pushpa Rawat and Anupama Srinivasan traces the lives of lower middle class and working class women in small industrial towns in India and their struggle as individuals, in terms of love, relationships and taking charge of crucial decisions in life. Where do the dreams of women feature? Do they feature at all? The film interestingly intersperses candid interviews with the older generation with those of the younger generation. Where the elders speak of caste and tradition, the younger women speak of suppression. Nirnay also brings out poignantly and powerfully, the power of the camera, of the transformation of the soft-spoken and vulnerable yet resilient and stubborn Pushpa, as she confronts these basic problem facing young women, armed with a camera.

As Pinki said, if one supports individuals and their right to exercise freedom of choice, the time to speak up is now. Whether it is in the workplace, in marriage, in love or in defining one’s gender. It really is upto the person concerned. It is their inalienable right.

Report – Paroma

Photography – Aniruddha

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!